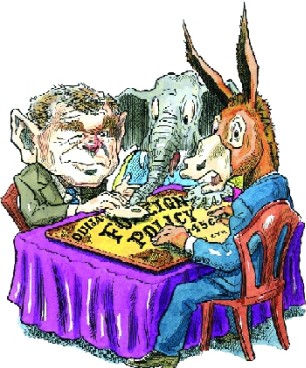

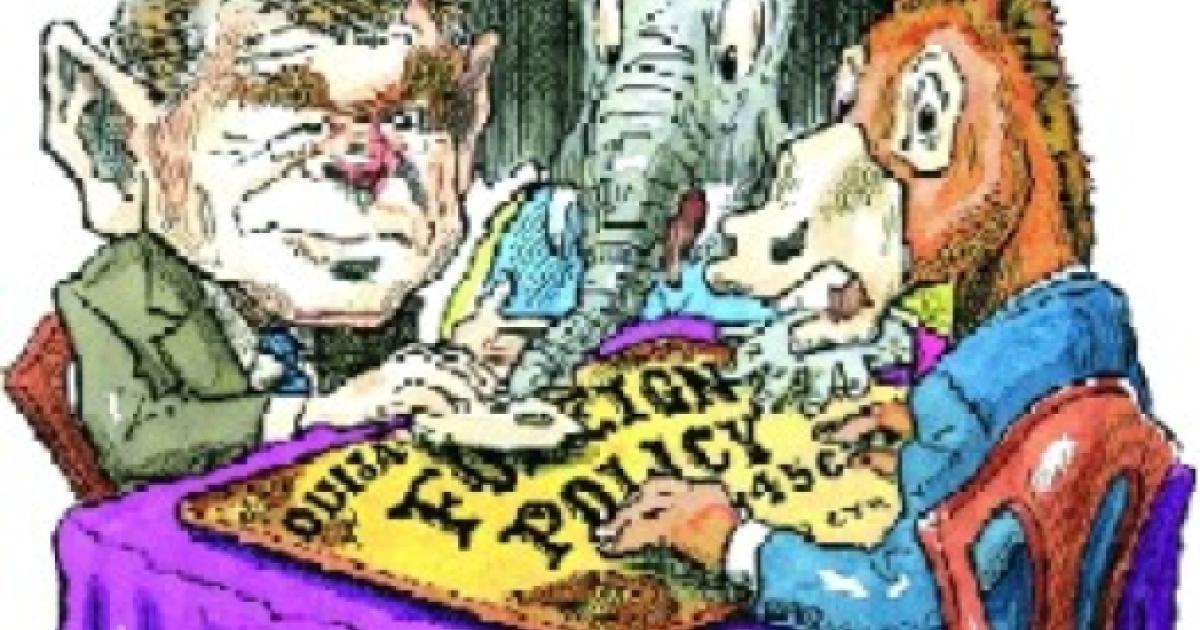

In foreign policy, Congress defers to the president. Why? Risk aversion. By David W. Brady and Craig Volden.

Sunday, July 30, 2006 4 min read By:

Old Master==

The terrorist attacks of 9/11 brought about a period of bipartisanship in Congress that lasted less than a year. It is not surprising that an act of war that kills nearly 3,000 people in America's major city would bring about a period of national unity. The decision by the government to go after the Taliban in Afghanistan was a popular and essentially noncontroversial choice. But the decision to go to war with Iraq was another matter: A significant minority of Americans and a majority of our European allies were opposed to military action in Iraq without a U.N. resolution authorizing the use of force. So why did President Bush get his way in Congress relatively easily? Why, despite the fact that a majority of Americans presently feel that the war is going badly, does the president get the appropriations he asks for? Why doesn't he face votes in Congress forcefully expressing displeasure with the situation in Iraq? In domestic politics Bush was thwarted on Social Security, making the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts permanent, and immigration policy, yet on Iraq he faces only verbal criticism, not legislative defeat. Why this difference between foreign and domestic policy?

Preserving the Status Quo

Put simply, with few exceptions, there is not much uncertainty in domestic policy relative to foreign policy. In domestic policy, members of Congress can accurately calibrate how shifts in policy will affect their district or state.

Washington, D.C., is a city of information, set up to let members know how thousands of interest groups and millions of citizens feel across almost all areas of domestic legislation. In the 109th Congress, within a few months of President Bush's State of the Union Address, every member of Congress had a good idea how hundreds of interest groups felt about the president's plan to privatize some Social Security funds.

In addition to all of the interest-group information that members receive on domestic legislation, there are literally hundreds of polls taken by and for members showing how Americans, including those in their state or district, feel about any given domestic issue. Thus members can compare interest-group information against public opinion polls, focus groups, and district meetings to determine how legislation will affect their long- and short-term career ambitions.

| Why, despite the fact that a majority of Americans presently feel that the war is going badly, does the president get the appropriations he asks for? Why doesn't he face votes in Congress forcefully expressing displeasure with the situation in Iraq? |

But in foreign policy there is much more uncertainty surrounding policy alternatives. There are many fewer interest groups in this arena, and public opinion is less predetermined, which allows the president as commander in chief and head of state to take the lead on policy formulation. The president's goal is clear—keep America and Americans safe—but the means are often controversial. Some view international institutions as the proper means for ensuring peace; others believe that we should have a strong military to protect our interests; still others believe that a combination of international institutions and force works best.

Additionally, in foreign policy much of the key information on a given issue is of a highly secure nature and is thus attached to the executive office. Consider the complicated nature of U.S. policy in the Middle East. Is the presence of U.S. troops in Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Afghanistan increasing the number of terrorists ready to attack us, or are the terrorists all in Iraq? Do the elections in Iraq and Palestine mean that democracy has a future in the region? Should the United States try to strengthen the United Nations, leave it as it is, or weaken it further? These are difficult questions when real information is often not present or in very small supply.

| After 9/11, because of the immense uncertainty about the world, members of Congress generally preferred that the president act first, act quickly, and act decisively. |

By and large, most Americans expect the president to resolve foreign policy crises such as the Iraq situation or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Because their constituents do not expect them to solve foreign policy problems, members of Congress can reasonably decide that not acting is a safer electoral choice than acting. Legislative inaction due to high uncertainty surely makes electoral sense, especially when the status quo doesn't seem too problematic.

After 9/11, because of the immense uncertainty about the world, members of Congress generally preferred that the president act first, act quickly, and act decisively. Indeed, much of the country looked to President Bush for leadership and offered him their support. The president experienced the well-known rally-around-the-flag effect. In late August 2001, CNN, Gallup, and Pew Research identified the president's job approval rating at a little more than 50 percent; on September 11 and 12, the New York Times had his approval rating at 76 percent. During the action in Afghanistan, the president's approval rating never dropped below 83 percent and was often as high as 90 percent.

The initial reaction of Congress toward U.S. policy in Afghanistan reflected the public's positive views of the president. There were several votes on Afghanistan. The most significant one, occurring on September 14, authorized the use of armed force against those responsible for the 9/11 attacks. In the Senate the vote was 98–0, and in the House it was 420–1 (Representative Barbara Lee of California was the sole no vote). Supplemental appropriations for the Afghanistan action also passed with bipartisan ease. The victory over the Taliban put the president's approval rating at 89 percent by the time of his 2002 State of the Union Address.

The steady march toward war with Iraq began to put some members under pressure to speak up about the role of Congress in the foreign policy process. By mid-July 2002, some members of the president's own party were pushing for a greater decision-making role. Republican Senators Arlen Specter and Chuck Hagel warned that there had to be a national dialogue on the issue to avoid some of the mistakes of Vietnam. Some House and Senate Democrats tried to use the appropriations committees as a way of affecting Iraq policy. Although some congressional noise about Iraq policy was present, it was evident to most members that they should vote with the president because that vote was easy to defend. There was a great deal of uncertainty over Iraq's intentions and weapons, and neither Congress nor the president controlled the status quo. That is, irrespective of what Congress might (or might not) do, the U.N. Security Council, the Arab world, and Al Qaeda were all going to take actions that would change the status quo.

| Because their constituents do not expect them to solve foreign policy problems, members of Congress can reasonably decide that not acting is a safer electoral choice than acting. |

Because members of Congress faced great uncertainty over the status quo, voting to support the president seemed the safest strategy for members of Congress who feared electoral retribution. Members from safe liberal seats could afford to object to the war in Iraq without affecting their electoral careers, but most members could not afford such a vote. Their strategy seemed to be to wait and see how things go: If the war went well, then they could tell voters that they'd voted with the president; if things didn't go well, they could object to the direction the president had taken and still be reelected. Given this risk-averse strategy of many members of Congress, it is clear why the president would go to Congress for a resolution authorizing force against Iraq, knowing victory was certain.

The House voted on October 10, 2002, on a resolution authorizing the use of force against Iraq. The final floor vote was 296–133, with 81 Demo-crats joining 215 Republicans to vote in favor—a significant show of bipartisan support. The next day, the Senate voted 77–23 to authorize the use of force. Of the 34 senators up for reelection, 31 voted for the resolution. In the end, liberals from safe districts or states were less uncertain about how a no vote would affect them and thus felt more comfortable voting against the resolution. Yet those Democrats up for reelection voted with the president much more frequently than those not up for reelection because it was an immediately safer bet.

Understanding why Congress has supported the president in the past makes predicting the future much easier. The 109th Congress will continue to vote in support of appropriations for the military and for the Iraq effort. There is still a great deal of uncertainty about U.S. policy and what the future will bring in Iraq and the Middle East. Will there be relative peace between Israelis and Palestinians? Will the newly elected Iraqi government bring stability and, if so, how soon? As long as answers to these questions and others like them are not clear, uncertainty prevails, which helps the president continue to win votes for his foreign policy.

Special to the Hoover Digest.